Nigeria's criminal justice reforms of 2015 promised to address serious problems such as pretrial detention. New tactics to ensure implementation of the law are underway with leadership from civil society, law student clinicians, and the donor community.

This is the final chapter in a four-part series on how access to justice build resilience in the Sahel. Read the introduction here.

As the recent killings of peaceful protesters in Lagos has underscored, Nigeria faces significant challenges to the rule of law — including widespread corruption, insecurity, and rights violations.1

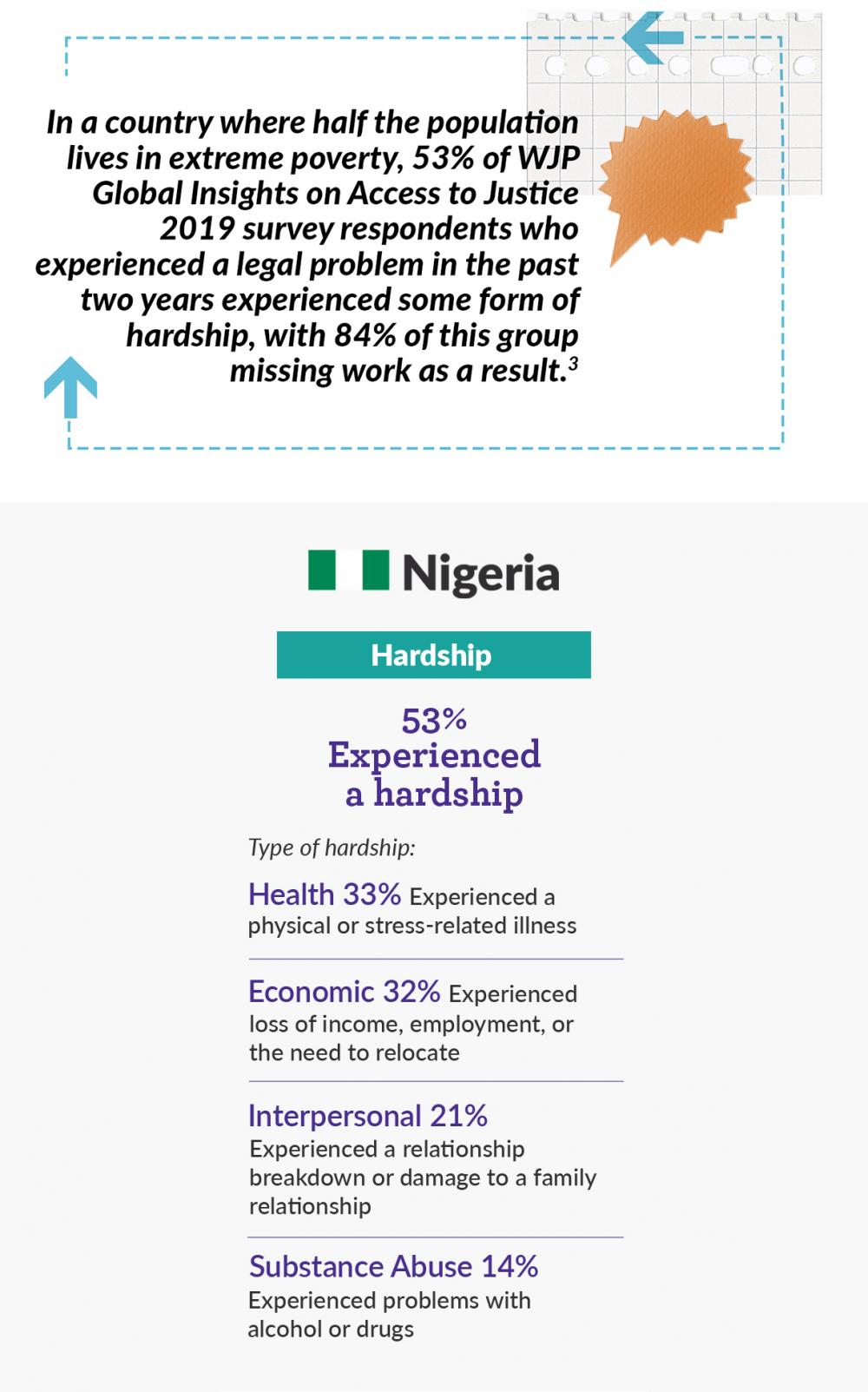

Less visible but no less important, ordinary Nigerians confront steep obstacles on their path to justice, including insufficient legal help and judicial processes that are slow and expensive.2 In a country where half the population lives in extreme poverty, 53% of WJP Global Insights on Access to Justice 2019 survey respondents who experienced a legal problem in the past two years experienced some form of hardship, with 84% of this group missing work as a result.3 Such disruptions undermine state legitimacy and threaten national security because the failure to deliver essential public services — particularly in the North where Boko Haram remains active — creates the conditions for mass unemployment, extreme poverty, and extrajudicial violence.4

Of particular urgency on the criminal justice front is the epidemic of pretrial detention, which delays justice and contributes to overcrowded prisons. More than two-thirds of people detained in Nigeria have yet to receive a trial — nearly twice the average for Africa as a whole and three times the rate for Europe.5 The state has held some inmates without trial for more than a decade, violating their fundamental rights to due process, clogging the judicial system, and exposing them to the continued risk of illness and torture.6

According to civil society actors interviewed by the World Justice Project, several factors have contributed to high rates of pretrial detention in Nigeria. Detainees often are held without bail due to outdated recordkeeping and insufficient legal representation at the time of arrest. Prison officials may not know the correct age or identity of some detainees, which can prolong detention and increase recidivism. In some cases, detention functions as a means to extract bribes or other improper payments. Unresolved civil disputes can prompt an aggrieved party to lodge a criminal complaint, gumming up the justice system.

In 2015, the Nigerian Parliament passed major legislation to reform the administration of criminal justice, including pretrial detention. This new statute, known as the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA), is intended to build official prosecutorial, prison, and judicial capacity at the federal level, reducing costly delays and protecting the rights of detainees. It comprises an important part of a comprehensive legal framework that, if fully implemented, could help bring the Nigerian justice system into compliance with international law.7

Transforming Nigeria's courts and prisons to adhere to the ACJA will prove a colossal undertaking. The ACJA replaces two existing statutes that had provided for a separate criminal justice process in the Northern states, helping to harmonize Nigeria's federal system.8 The ACJA also calls for new technical systems, including a Central Criminal Records Registry; imposes new timelines for recording and reporting arrests, hearing bail requests, and inspecting places of detention; and most significantly, limits the use of remand and establishes time limits on detention.9 Further complicating matters, Nigeria is a federal system wherein sovereignty is shared between the states and the national government. Individual states must therefore adopt the ACJA for it to take effect.10 Putting all of these measures into practice will require sufficient funding, effective coordination, and political will.

To hasten these reforms, the ACJA established a monitoring committee with representatives from government and civil society.11 The Administration of Criminal Justice Act Monitoring Committee (ACJAMC) meets regularly in Abuja, where it resolves issues pertaining to adoption and implementation. Members include academic institutions, non-governmental organizations, local charities, and legal defense funds. The ACJAMC gives these civil society actors an opportunity to dialogue with officials from the federal courts, the police, and the corrections system and provides a conduit for training young legal professionals.

Many of the reform elements related to implementing the ACJA have been supported by a Big Bet from the MacArthur Foundation. It aims to reduce corruption in Nigeria by supporting "Nigerian-led efforts that strengthen accountability, transparency, and participation."12 Their approach to social accountability pairs "enabling environments for collective action" with "state capacity to respond to citizen voice."13 Key to this theory of change are tactical pilot programs that can demonstrate the positive impact of reform, sparking innovation and motivating leadership in other sectors of government.

One effective tactic in the effort to reform pretrial detention has been the use of legal education. At the level of institutional reform, a network of law schools and civil society organizations is working to build capacity and increase adherence to official procedures. While at the grassroots level, a cross-sector collaboration is raising awareness and equipping detainees to navigate the trial process.

A top-down example is the Reform Kuje Prison Project currently being implemented by New Rule, Partners West Africa Nigeria, and the Network of University Legal Aid Institutions in Nigeria. Funded by the U.S. Department of State's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL), this project pairs law student clinicians with pro bono attorneys to help streamline administrative procedures, protect the rights of the accused, and reduce the use of pretrial detention in one medium security prison where 82% of detainees are awaiting trial.14 Although they are not qualified to represent clients, students can interview detainees, prepare motions, and provide oversight for the system's new inmate-tracking database. Law student clinicians lend teeth to the ACJA, because they empower officials to honor new limits on the scope and duration of pretrial detention. Knowing the age and case history of each detainee helps court officials intervene to end improper detention, prioritize the release of low-risk offenders, and prevent juveniles being charged as adults.

Likewise, legal education programs can help lend "voice" to those most impacted by the ACJA — detainees themselves. One creative example is the Informal Justice Court currently being implemented by the Aardschap Foundation, in partnership with local civil society organizations, in Lagos's Ikoye Prison. Pairing informal legal training with citizen theatre, this project will allow pretrial detainees to rehearse their own cases before a court of their peers, acclimating them to the trial process before they ever stand before a judge. Their stories will also be featured in art installations in Nigeria and the Netherlands, helping to spread awareness about the issue.

These projects and other participatory education initiatives help bridge the gap between legal frameworks and actual practice on the ground. To learn more about these efforts and related data from the WJP, please view a video recording of our recent workshop on Legal Education: Reforming Pre-Trial Detention in Nigeria.15

NEXT > Leveraging Informal Justice: How to Counter Descent-Based Slavery in Mali

1 At present, Nigeria ranks 108 of 128 countries measured by WJP Rule of Law Index. When compared with other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as lower middle-income countries as a group, it scores well below average on several rule of law factors — including absence of corruption, fundamental rights, order and security, and regulatory enforcement. Other sub-factors reveal erratic results: Nigerian civil justice is subject to unreasonable delays, and criminal justice underperforms on freedom from corruption, timely and effective adjudication, and due process and rights of the accused. See World Justice Project, WJP Rule of Law Index 2020, https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/country/2020/Nigeria/

2 In a national poll, 60% of Nigerians reported experiencing a legal problem in the prior two years. Among the 40% of respondents within this group who considered their problem done and fully resolved, the resolution process took 14.2 months on average. See World Justice Project, Global Insights on Access to Justice 2019, http://data.worldjusticeproject.org/accesstojustice/#/country/NGA.

3 ibid. For data on the prevalence of extreme poverty, see World Bank, World Development Indicators, Poverty Headcount Ratio, Poverty Headcount Ratio at $1.90 a Day (2011 PPP) (% OF POPULATION), http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

4 Daniel A. Tonwe & Surulola J. Eke (2013) State fragility and violent uprisings in Nigeria, African Security Review, 22:4, 232-243, DOI: 10.1080/10246029.2013.838794.

5 Open Society Foundations, "Improving Pretrial Justice: The Roles of Lawyers and Paralegals," 2012, p. 30 https://www.justiceinitiative.org/publications/improving-pretrial-justice-roles-lawyers-and-paralegals

6 ibid.

7 Articles 9 and 10, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 12 April 2019, CCPR/C/NGA/Q/2/Add.1 https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx

8 Rose Ugbe, A Critique of the Nigerian Administration of Criminal Justice Act 2015 and Challenges in the Implementation of the Act, AFLCLJ 4 (2019), p. 70 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341313899_A_CRITIQUE_OF_THE_NIGERIAN_ADMINISTRATION_OF_CRIMINAL

_JUSTICE_ACT_2015_AND_CHALLENGES_IN_THE_IMPLEMENTATION_OF_THE_ACT

9 supra ACJA 2015, Part 30

10 To date, 29 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) have assented to the ACJA. Local versions have yet to pass in many northern states — including Borno, Gombe, Katsina, Kebbi, Niger, Yobe, Taraba, and Zamfara. See ACJL Tracker at https://www.partnersnigeria.org/acjl-tracker/

11 supra ACJA 2015, Part 46

12 The foundation has awarded $66.8 million across 138 grants from 2015-2019 as part of their On Nigeria strategy, which aims to transform Nigerian criminal justice from above and below. For a discussion of the "clear line of site" on criminal justice reform indicators, see the 2019 Monitoring and Evaluation Report, available at https://www.macfound.org/press/evaluation/nigeria-big-bet-2019-annual-report/

13 Fox, Jonathan A. "Social Accountability: What Does the Evidence Really Say?" World Development 72 (August 2015), 346-361. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X15000704

14 https://www.partnersglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/wpallimport/files/Kuje-one-pager-FINAL.pdf

15 Conducted in partnership with the Aardschap Foundation for the Knowledge Platform for Security and Rule of Law (KPSRL) Annual Conference 2020.

Support for "Access to Civil Justice in the Sahel" has been provided by the Knowledge Management Fund, a program of the Knowledge Platform Security & the Rule of Law at the Clingendael Institute for International Relations, Netherlands.