2015 set a new record for displaced populations worldwide: 59.5 million people. Compared to the 24 million people displaced by the Second World War, today’s numbers lead governments to revisit their current urban planning paradigms.

2015 set a new record for displaced populations worldwide: 59.5 million people. Compared to the 24 million people displaced by the Second World War, today’s numbers lead governments to revisit their current urban planning paradigms.

In the past, we have seen human ingenuity play a role in humanitarian approaches to build better, more complete cities from ruins. However, when massive flows of displaced populations and economic migrants flock towards cities today, we tend to see a defensive reaction instead of a humanitarian response. As a consequence, cities around the world are experiencing a rise in the number of slums due to a lack of formal housing options for migrants, who are forced to compete for scarce resources like water, land, and jobs. Instead of implementing urban planning schemes that promote equal opportunity for adequate housing, developers and urban planners are preoccupied with increasing property values, which ultimately results in higher rates of eviction and creates a neglected underclass.

To put an end to this dehumanizing trend, the program “Participlan” has worked with a variety of stakeholders to develop a framework for inter-institutional and inter-cultural dialogue between governments, communities suffering from inadequate housing rights, and their neighbours. Together, the NGOs, Microenergia, Techo (formerly Un Techo para mi PaÃs), PROCASHA, and Red de Acción Comunitaria, as well as communities and local governments in Argentina and Bolivia and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), have created a model for involving segregated, low-income communities in urban planning initiatives.

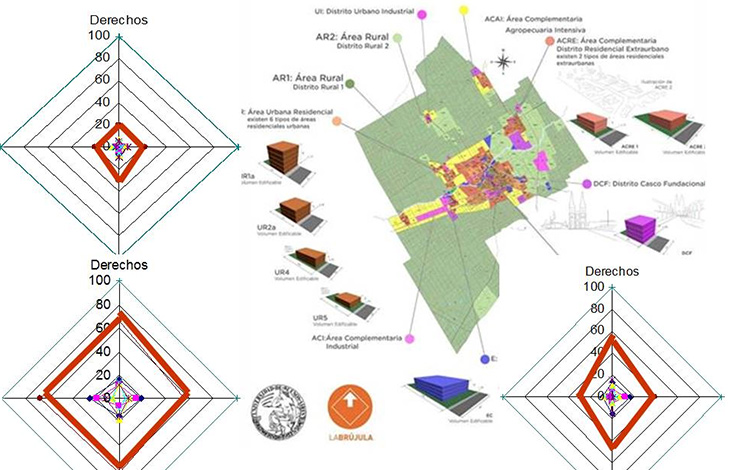

To successfully implement Participlan, we found the use of the “Compass” activity – a methodology that measures human rights fulfilment – to be crucial. “Compass” is comprised of four analyses that are collaboratively completed by residents and participating NGOs to produce a quadrangle graphic reflecting the particular condition of a slum as compared to the rest of the city, which helps to identify priorities and develop action plans.

The Compass methodology includes a broad range of variables in its analysis: the “north” portion of the quadrangle measures the extent to which residents’ right to adequate housing, land, water, public services, and jobs is legally guaranteed in a given slum. The “south” portion of the quadrangle measures the extent to which the state and communities support these rights in practice. The “east” portion of the quadrangle measures the adequacy of urban regulatory frameworks, and the “west” portion looks at the provision of public works. In combination, these four portions of the quadrangle provide a comprehensive diagnosis of the state of housing rights in a given slum.

Multiple cities were involved in the Compass exercise during the implementation of Participlan program. Lujan, a city at the edge of the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, saw positive change when it completed the Compass exercise. For example, Lujan implemented a participatory review of the city planning code, which drastically minimized the number of gated communities to be developed in wetlands, as these areas were found to cause recurrent flooding in surrounding slums. In Escobar, a slum in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires called “Los Pinos,” residents built and maintained the infrastructure for basic sanitation, waste and water management, pavement, and street lighting. The impact of these upgrades to their neighbourhood has encouraged and empowered residents to pursue a land regularization process to obtain secure land tenure, and has been highlighted as a best practice in the World Migration Report.

In the tourist city of Salta, where the proliferation of slums along the riverside has led to recurrent flooding, communities and local government officials participated in the Participlan program in order to develop a strategy to build resilient housing for low-income migrant communities. The Participlan program has developed a way to integrate insights and skills of slum residents into the urban fabric, resulting in vital dialogue between slums, the municipality, and the private sector.

In addition to the successes in Argentina, the Participlan program was also active in Cochabamba, Bolivia, where a consultative process highlighted overcrowding, lack of access to water, non-secure land tenure, and discrimination against women as major threats to residents’ housing and fundamental human rights. Unauthorized settlements in Cochabamba are characterized by the presence of multiple ethnic groups that have migrated from different regions of the country, introducing language and cultural barriers that fragment the city’s slums. However, participatory workshops that allowed community leaders and representatives from the local government and private sector to discuss and ultimately agree to address human rights deprivations saw positive and inspiring results.

For example, collaboration between residents, community leaders, and the government in an unauthorized settlement called “Plan 700” resulted in 48 households receiving expanded housing to accommodate extended families and address the issue of overcrowding. The municipality considers the upgrades carried out by PROCASHA after using the Compass methodology to be successful. Furthermore, a land regularization process to secure land titles is also ongoing. Once complete, this will allow residents to connect their homes to water networks, a critical problem for many informal settlements.

While Participlan has certainly seen the benefits of implementing a participatory model, it has not always been easy. For one, we find ourselves struggling with public and private entities that resist the idea of integrating human rights as a foundational principle for developing real estate. In addition, the solutions developed through this program are not cheap. They may require some municipalities to give up land value capture and business opportunities. However, these battles are the cornerstone of a new urban planning paradigm – one which understands that migrants are a key stakeholder in addressing slum proliferation; integrates human rights as a foundation to urban planning; and empowers slum dwellers as active stakeholders in the creation of sustainable solutions, rather than passive and segregated aid recipients.

By bringing the human rights approach to city-planning, cities are able to gain the human touch that ultra-modern, sophisticated, and fragmented territories are unable to attain, while also achieving the the dignity, justice and happiness for its residents.